I woke, as if from a dream (a bad dream). When I saw the photos, I doubted by eyes. The images and plant list suggested a far richer woodland than I’d ever seen - but which I had long looked for, far and wide.

But Yikes! It had recently been bulldozed, in part. Yet – more important – the treasure mostly still existed in this world. Botanist Dan Carter called the site "jaw-droopingly intact." Conservationist Eriko Kojima, on seeing it for the first time, was so blown-away she declared that she "wouldn't sleep for a week."

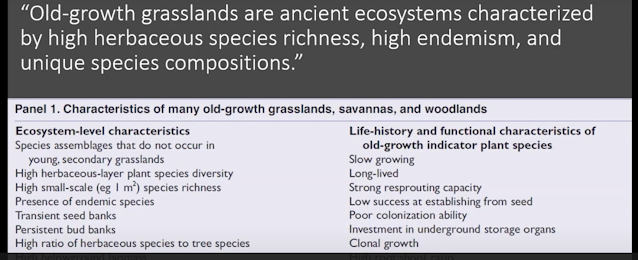

Oak woods had seemed dull. Compared to prairies, savannas, or fens – these days the woods excite few natural areas conservationists. The word biodiversity is currently hot; it invokes the tropical rain forest, the prairie white-fringed orchid, coral reefs - but not woods.

For context, consider the re-discovery of the prairies and savannas. Only in recent decades did prairie impinge on public consciousness, when John Curtis, Aldo Leopold, May Watts, Robert Betz and a few others opened our eyes. (See Endnote 1: The Re-discovery of Nature.) Now we know that original prairie remnants are extremely rare and rich. If you’ve never had the experience, it’s worth learning to identify the plants and to perceive the structure so you can truly see one. An original prairie is strikingly superior in plant and animal biodiversity to degraded remnants or restorations. We’re learning to care for and expand remnants, but a reconstruction is nothing like an original.

The discovery of the savanna was unexpected and yet more recent. Even in the 1970s, the Illinois Natural Areas Inventory essentially didn't find them, in part because they're rarer than the prairies and in part because no one had yet learned what to look for. (A good start at belatedly recognizing the savanna emerged from the 1994 North American Conference on Savannas and Barrens.)

But now for true remnant woodlands. Did woods of high quality still exist - especially bur oak woods, the tree that requires the most sun, according to Curtis? Can we study them only through restoration? But now the "discovery" and recognition of the quality of the little bur and white oak Army Lake site goes down into history? How big a discovery is it?

Individual endangered species have the advantage of being somewhat protected by laws, regulations, and standard practices. But – rarer and more important – a very high quality woodland ecosystem is not so protected. (See Endnote 2. Learning from Army Lake.)

|

| One of the photos that seemed marvelously rich for a woodland. Largely high-quality and rare plants make up this turf, including yellow star-grass, robin’s-plantain, forked aster, wood pea, veiny pea, wood betony, low false bindweed, sky-blue aster, wood rush, Penn sedge, running savanna sedge, and blue-eyed grass. (2016 photo by Dan Carter) |

Most woodlands today, if they have any quality at all, impress people who care by their dense displays of common spring ephemeral flora. In contrast, Army Lake Woodland has a dense, diverse, rare flora throughout spring, summer, and fall. That it's principally not ephemeral. Because of grazing or excessive shade at some point, most woodlands have lost most high-quality plants - especially those of summer and fall - as well as the other biota (animals, fungi, bacteria, etc.) associated with them. (See Endnote 3.)

“A gut punch ... a failure ... a hill worth dying on.”

I personally heard about the site in 2022 when Christos Economou sent me a link to a remarkable 2020 blog post by the perceptive Dan Carter. I didn't know the man. Later, in response to inquiries, Dan expressed two regrets: 1) as a scientist, he regretted that he wrote that post when he was emotional with anger at the destruction; 2) as a person, he wished he'd been more outspoken in defending the site from development, though it would likely have cost him his job. Many eco-experts work for public agencies, or otherwise get funded by them, or just need to cooperate with them. They speak calmly. When the damage came, it was worse than Dan or his colleagues expected. Dan called it "a gut punch." In retrospect a battle to save this woods would have been "a hill worth dying on." (See Endnote 4: Politics.)

Central to what makes a Grade A prairie remnant striking is the density and diversity of rare plants. When Dan Carter was asked to evaluate Army Lake Woodland as a potential site for a boat launch, he found a woodland as rich as a remnant prairie. (See Endnote 5. Plant Species List.) The plants are important in themselves, but they're also the best indicators of full biodiversity that includes the invertebrates, fungi, bacteria and other biota that are principally associated with true, rich remnants because those organisms rely on the plants. .

Army Lake Woodland had a substantially more diverse and high-quality woodland community than is known anywhere else in southeastern Wisconsin (perhaps anywhere in Wisconsin or northern Illinois?). So, how could it get bulldozed by a conservation agency, when that boat launch could have been put on many other spots on the shore of Army Lake? Recommendations were not followed. Insufficient advocacy and public concern emerged. About a third of this best woodland remnant was destroyed. That's the bad part. But, again, two-thirds of this gem and quite a bit more restorable remnant still exist.

Next Steps

In the conservation of small remnants, there are typically three values and associated goals:

1. Save, restore, and study what's there.

2. Expand the size of the remnant, if possible, as small plant and animal populations are vulnerable.

3. Use seed and knowledge to restore larger areas.

1. Save, restore, and study

An anticipated program of restoration management is crucial, as increasing shade and invasives threaten more and more quality. The site has to date received no invasives control and no prescribed burns. WDNR staff resources are stretched thin and deserve higher appropriations. But volunteer stewards could carry a lot of the load on this small site, if properly facilitated and empowered. Needed stewardship would likely lead to additional species emerging, knowledge, and insights.

2. Expand

The high-quality remnant biota could be restored into poorer-quality adjacent areas. A first step that could start any time would be invasives control. Crown vetch has recently been discovered along the boat launch access road. Many dangerous invasives are there in small numbers. They should go soon. Some native species now cast damaging amounts of shade, in the absence of fire. Regular controlled burns are a must. Many managers would recommend annual burns of half or more of such a site, at least while it's in the "intensive care ward" stage.

3. Use seed and knowledge to restore larger areas.

Can-do management and restoration of Army Lake Woodland would benefit other nearby remnants (and needy oak woodlands throughout the midwest), in part by what could be learned here in the next few years. Also, many nearby areas would benefit from seed from Army Lake, especially once it has recovered overall quality.

Most of the diversity on the island survives where over-growth by brush has been limited, perhaps due to the intense competition of diverse grasses and wildflowers.

Most of the diversity on the island survives where over-growth by brush has been limited, perhaps due to the intense competition of diverse grasses and wildflowers.Additional views of the rich flora of Army Lake Woodland are below:

Blooming in the center of this photo is the formerly common pale vetchling with its cream-colored blossoms. Also in bloom here are wood betony (yellow), shooting star (white), and wild geranium (pink).

Blooming in the center of this photo is the formerly common pale vetchling with its cream-colored blossoms. Also in bloom here are wood betony (yellow), shooting star (white), and wild geranium (pink). "I contacted some local stakeholders and advised them of a public meeting (listening session or some such thing) about the launch, warning about potential impacts to something precious and irreplaceable, and I promptly got an upset phone call from the property manager (though I appreciate him not going straight over my head like the Milwaukee County Parks Natural Areas Coordinator did a few years later). In hindsight, I kind of wish he had called my boss. It might have freed me up to more strongly oppose what was about to happen."

"What happened at Army Lake wasn’t just wrong, it was insane. Really, the forked aster was the only thing there with protected status that might have helped it, but that’s also insane, because communities support rare species; it’s not the other way around."

As Dan points out, the kind of public support that might have made the stakes clearer to decision makers – perhaps to a point that Dan would not have felt his job in jeopardy – was lacking. A strong constituency for Army Lake Woods’ biodiversity might, in fact, have allowed conservationists to feel empowered to look for creative potential solutions. A key question is, how do we caring conservationists build such constituency?

| |

Acer saccharum | hard maple, sugar maple (an invader?) |

Agrimonia gryposepala | common agrimony, tall hairy agrimony |

Amelanchier laevis | Allegheny serviceberry, Allegheny shadblow |

Amphicarpaea bracteata | American hog-peanut, hog-peanut |

Anemone americana | round-lobed hepatica |

Anemone quinquefolia | nightcaps, wood anemone |

Antennaria parlinii | Parlin's pussy-toes, plantain pussy-toes |

Apocynum cannabinum | hemp-dogbane, Indian hemp |

Aquilegia canadensis | Canadian columbine, red columbine, wild columbine |

Aralia nudicaulis | wild sarsaparilla |

Asclepias exaltata | poke milkweed, tall milkweed |

Aureolaria grandiflora | large-flowered yellow false foxglove |

Berberis thunbergii | Japanese barberry |

Calystegia spithamaea | low bindweed, low false bindweed |

Carduus nutans | musk thistle, nodding thistle (an invader) |

Carex cephalophora | oval-headed sedge, short-headed bracted sedge |

Carex pensylvanica | common oak sedge, Pennsylvania sedge |

Carex siccata | dry-spiked sedge, hay sedge, hillside sedge, running savanna sedge |

Carex stricta | tussock sedge |

Carya ovata | shagbark hickory, shellbark hickory |

Ceanothus americanus | New Jersey tea, red-root |

Celastrus scandens | American bittersweet, climbing bittersweet |

Cerastium fontanum | common mouse-ear chickweed |

Comandra umbellata | bastard-toadflax, false toadflax |

Cornus foemina | gray dogwood, northern swamp dogwood, panicled dogwood |

Cornus rugosa | round-leaved dogwood |

Cornus sericea | red osier dogwood |

Dactylis glomerata | orchard grass |

Danthonia spicata | poverty danthonia, poverty grass, poverty oat grass |

Diervilla lonicera | northern bush-honeysuckle |

Elaeagnus umbellata | autumn olive |

Equisetum arvense | common horsetail, field horsetail |

Erigeron pulchellus | Robin's-plantain |

Euphorbia corollata | flowering spurge |

Eurybia furcata | forked aster |

Festuca saximontana | Rocky Mountain fescue |

Fragaria virginiana | thick-leaved wild strawberry, Virginia strawberry, |

Frangula alnus | European alder buckthorn, glossy buckthorn |

Fraxinus americana | white ash |

Galium boreale | northern bedstraw |

Galium concinnum | pretty bedstraw, shining bedstraw |

Gaylussacia baccata | Huckleberry |

Gentianella quinquefolia | ague-weed, stiff gentian |

Geranium maculatum | Crane's-bill, spotted geranium, wild geranium |

Helianthus hirsutus | hairy sunflower, oblong sunflower, rough sunflower |

Heuchera richardsonii | prairie alumroot, Richardson's alumroot |

Hieracium caespitosum | field hawkweed, yellow king-devil |

Hieracium umbellatum | narrow-leaved hawkweed, northern hawkweed |

Ilex verticillata | common winterberry |

Juniperus virginiana | eastern red-cedar |

Krigia biflora | false-dandelion, orange dwarf-dandelion, two-flowered Cynthia |

Lactuca canadensis | Canada lettuce, tall lettuce, tall wild lettuce, w |

Larix laricina | larch, tamarack |

Lathyrus ochroleucus | cream pea-vine, pale vetchling, white pea |

Lathyrus venosus | veiny pea |

Lonicera dioica | limber honeysuckle, mountain honeysuckle, red hone |

Lonicera X bella | Bell's honeysuckle, showy bush honeysuckle |

Luzula multiflora | common wood rush |

Maianthemum racemosum | false Solomon's-seal, false spikenard, large false Solomon's-seal |

Medicago lupulina | black medick |

Melilotus albus | white sweet-clover |

Melilotus officinalis | yellow sweet-clover |

Ostrya virginiana | eastern hop-hornbeam, ironwood |

Parthenocissus inserta | grape woodbine |

Pedicularis canadensis | Canadian lousewort, forest lousewort, wood-betony |

Phryma leptostachya | American lop-seed |

Picea glauca | white spruce |

Plantago major | broad-leaved plantain, common plantain |

Poa compressa | Canada bluegrass, wiregrass |

Podophyllum peltatum | May-apple, wild mandrake |

Polemonium reptans | Greek-valerian, spreading Jacob's-ladder |

Populus grandidentata | big-tooth aspen, large-toothed aspen |

Potentilla simplex | common cinquefoil, old-field five-fingers |

Prenanthes alba | lion's-foot, rattlesnake-root, white-lettuce |

Primula meadia | eastern shooting-star, pride-of-Ohio |

Prunus serotina | wild black cherry |

Prunus virginiana | chokecherry |

Pteridium aquilinum | bracken, bracken fern |

Quercus alba | white oak |

Quercus rubra | northern red oak |

Ranunculus abortivus | little-leaf buttercup, small-flowered buttercup |

Ranunculus fascicularis | early buttercup, thick-root buttercup |

Rhamnus cathartica | common buckthorn, European buckthorn |

Rosa carolina | Carolina rose, pasture rose |

Rosa multiflora | multiflora rose |

Sanicula marilandica | black snakeroot, Maryland sanicle |

Sisyrinchium albidum | common blue-eyed grass |

Solidago speciosa | showy goldenrod |

Solidago ulmifolia | elm-leaved goldenrod |

Symphyotrichum laeve | smooth blue aster |

Symphyotrichum oolentangiense | sky-blue aster |

Symphyotrichum urophyllum | arrow-leaved aster, white arrowleaf aster |

Taraxacum officinale | common dandelion |

Toxicodendron rydbergii | Rydberg's poison-ivy, western poison-ivy |

Trifolium pratense | red clover |

Vaccinium myrtilloides | velvet-leaved blueberry |

Viburnum opulus | European cranberry-bush (an invader) |

Viburnum rafinesquianum | arrow-wood, downy arrow-wood |

Vicia caroliniana | Carolina vetch, pale vetch, wood vetch |

Viola sororia | door-yard violet, common blue violet, hairy wood violet |

Vitis riparia | frost grape, river bank grape |

7 comments:

The plant list from the timed meander was actually from Milwaukee Public Museum fellowship work I did just after the launch went in. I looked at some other oak woodland and savanna sites similarly situated on islands or otherwise of good quality.

I think being on knolls open to all sides (at least before the brush finally did get worse), is important. Its common to some of the other sites like this but not quite as good that I know (out in the wetlands between Lulu and Eagle Spring lakes and out in the wetlands around Summit Bog. Wind tends to blow more of the litter clear, so in fire exclusions effects, particularly on the low, early flora are less severe. In the Driftless Area, the same phenomenon seems to occur on ridges, where the better woodland flora remains in areas where oak leaves tend to be exported vs. deposited. As Army Lake has gotten markedly brushier over the last several years, it is noticeable how more oak leaf litter is staying in place, and the flora is becoming more sparse.

This reminds me of the many times it was left to the staff of the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission, an independent state agency with state law to back it, to stand-up to other public agencies to protect a rare natural area on public land. We did not need o worry about losing our job, but getting the Park District Board or IDNR site manager to listen was always a problem. It was the threat of a campground going into a natural area at Apple River Canyon that spurred George Fell to come up with the concept of the Illinois Nature Preserves system, overseen by an independent Commission. Public employees who speak-up to protect nature are true heroes! But, they can't be expected to do it all alone. Every state needs a Friends of Illinois Nature Preserves or The Prairie Enthusists to advocate for nature.

From Will Overbeck:

There are a few woodlands like this one in the Kettle Moraine section of the NE Morainal Div. of IL. Of course with more invasive species... But ready for restoration stewardship when you are ready to organize! Let me know...

It is interesting to read that the dense diversity prevents the invasion of brush. And I am interested to read in the comments that flora becomes sparse when oak leaf litter stays in place. I guess that means you need to burn in order to have flora?

I am glad that Stephen Packard and Dan Carter finally met one another--and I am glad that the Army Lake Woodland was a focal point. I am fortunate to have visited the site on a number of occasions and, with Kettle Moraine Land Trust, to have helped advocate for its protection and management. Carry on your Great Work!

The tamarack swamp on the southwest side of the island is likely keeping the island cooler than nearby upland woods. When the surface of my lawn is 120 degrees F in the sun, the surface of my bog gardens are only 85 degrees because of evaporative cooling. When the cool air from the tamarack swamp blows to the island, the air is warmed evaporating moisture. These would make the island at Army Lake both cooler and drier than nearby upland woods. This would have helped preserve it as a relic from a former climate. There is a similar situation in the ravine at Deer Grove Forest Preserve, Cook County that has many of the same species but in a more degraded condition.

The abundance of legume species at this site is impressive. Army Lake Woods must have escaped the increases in soil nitrogen that have impacted many natural areas. Since a boat ramp was installed, I must wonder how long it will be before earthworms invade changing the soil in a manner that favors invasive plants.

In response to the comment on litter. Yes, it needs fire to remove that litter, especially now that brush has increased to where it is sheltering the woodland so the litter doesn't blow away. I think the site was resistant to fire exclusion for so long, because much litter was blowing off, so removing brush will help that too. I know another less diverse, but still unmanaged and miraculously open site near me where the wind blowing litter off phenomenon is obviously in play, allowing bastard toadflax and grove sandwort to continue a dense, healthy existence. It's also a common and pretty obvious phenomenon points at the ends of ridges in the driftless area, which is kind of a hot spot for nicer remnant oak woodlands that are holding onto more non-ephemeral early ground flora.

Post a Comment